Discover all the news and articles from TNUMIS Magazine exclusively

The Chameau Treasure

In the 16th century, Jacques Cartier began exploring Canada on behalf of France. At the beginning of the 17th century, the first fort, called “Quebec”, was established and colonization truly began under Louis XIV, when Canada was declared a French province. The maritime connections between the two continents became regular and essential to the economic strategy. The story of the Chameau treasure takes place in this historic setting.

Le Chameau: a French ship facing the storm

A military ship

Le Chameau (The Camel) was a military flute of the French Royal Navy. It was built in 1717-1718, in Brest, by the shipbuilder Étienne Hubac. The ship was intended to provide maritime links with French Canada during the reign of Louis XV. In these times of peace, it was not assigned to battle but was still equipped with weapons.

Between 1718 and 1724, the Chameau made an annual round trip between France and Quebec, carrying equipment, supplies and passengers.

The last crossing of the Chameau

In July 1725, the ship left the port of Rochefort for the sixth and last time, under the command of Captain Saint-James. It carried goods, ammunition and money to pay the French garrisons and the expenses of the colony. More than 82,000 pounds in gold and silver coinage were mentioned. The ship carried 100 officers and 216 passengers.

The voyage across the Atlantic Ocean was being uneventful when, close enough to its destination, off Cape Breton Island, the Chameau faced a storm. It hit a rock and capsized. It sank a few miles away from Louisbourg on August 26, 1725 with no survivors. Causing major human and material losses, this shipwreck was an absolute tragedy for Canada. At the time, the economic health of Canada was largely dependent on French supplies.

The beginning of a treasure hunt

The next day, the wrecked ship had easily been identified by finding debris washed ashore. Looters rushed to search for the wreck and its treasures. The Intendant Jacques Le Normant de Mézy had the place watched over and promised a third of the income from the sale to the person who would bring back all the belongings. He wrote to the governor of New France: “for the 35 years that I have been going to sea, I have never seen or heard of such an extraordinary shipwreck.”

The Chameau Treasure: the quest of a lifetime

The first explorations after the shipwreck

Captain Pierre de Morpain, an expert in marine salvage, surrounded himself with two Canadian divers, Antoine Fustier, nicknamed “Sent le vent” (“Smells the Wind”) and Pierre Poittevin, alias “La tempête” (“The Storm”), to search for the priceless jewel. They quickly identified the precise location of the shipwreck and drew up a map. They tried several times to recover the treasures, but the icy waters and the wreckage strewn over a wide area did not make the job easy. They failed and failed again. As the time passed, so did the troubles of history, and the Chameau treasure became a forgotten legend.

The excavations of the adventurer Alex Storm

Only two centuries later, the Canadian adventurer Alex Storm became interested in the Chameau treasure. From 1961 on, he documented, researched and acquired equipment with a single idea in mind: to discover the long-lost wreck.

After several unsuccessful attempts with the crew of the Orbit ship, he collaborated with two of his compatriots, David MacEachern and Harvey MacLeod. In 1964, they obtained from the government the “Treasure trove Act” which gave them the right to search for the treasure for three years and compelled them to repay 10% of the value of the discovery. They established a precise contract between them to define the sharing.

They mapped out their research, but the work took up to several months. Bad weather conditions, agitation and sea temperature made the project difficult. Alex Storm recounts his adventures and his quest for the Chameau treasure in Canada’s Treasure Hunt (1968): “We spent hours shivering in front of a tiny stove in the shelter of the wheelhouse, but we persevered.”

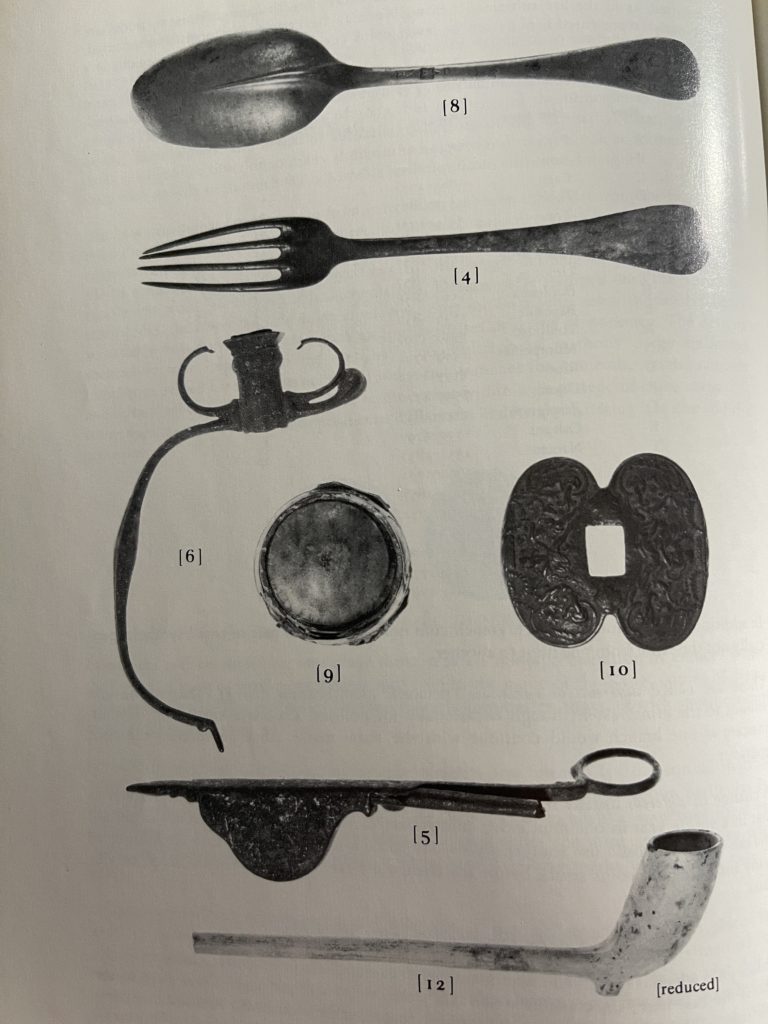

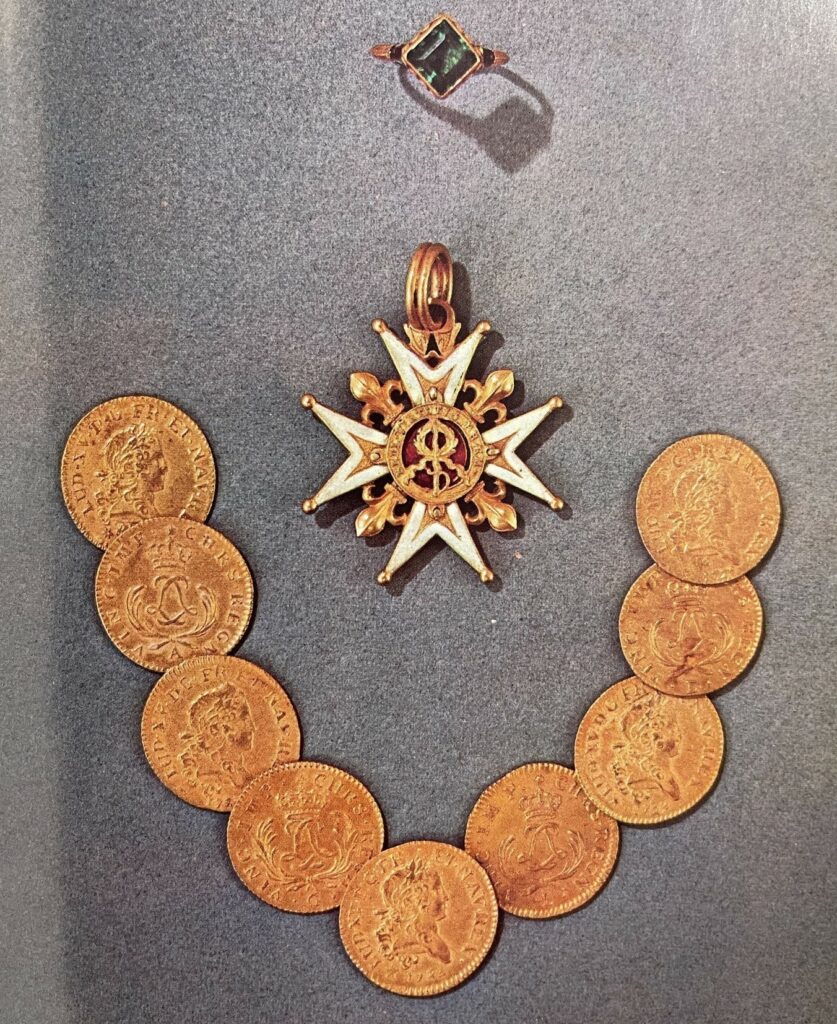

On September 19, 1965, the seabed excavations bore fruit. Gold and silver coins, jewels and other precious objects including a cross of the Order of St. Louis were hidden at about 30 meters depth.

Lawsuits were brought against Alex Storm by some of his early collaborators, but he was finally recognized as the owner of 75% of the treasure.

The collection of the archaeological jewel

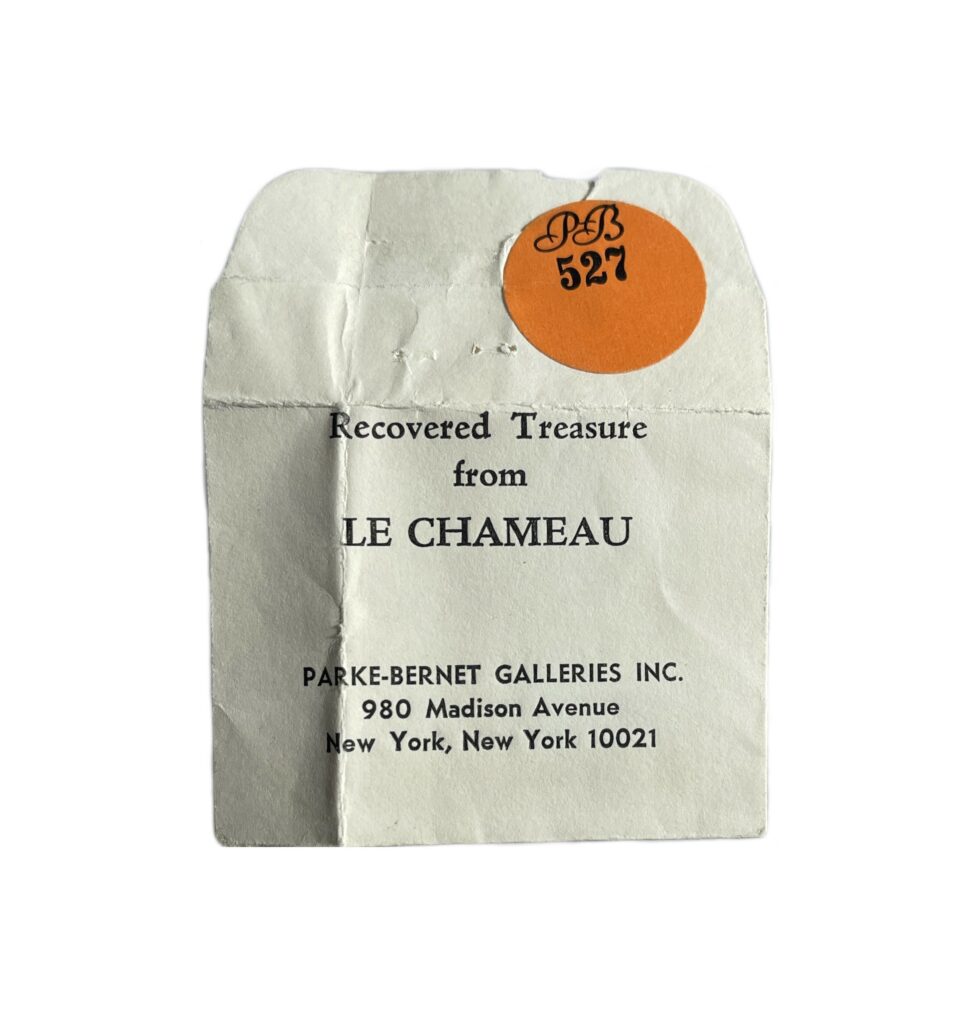

Part of this numismatic historical treasure was put up for sale by Sotheby’s New York on 10th and 11th December 1971, during an auction that would become famous. It brought in over $200,000.

The Salt Water gold and silver coins

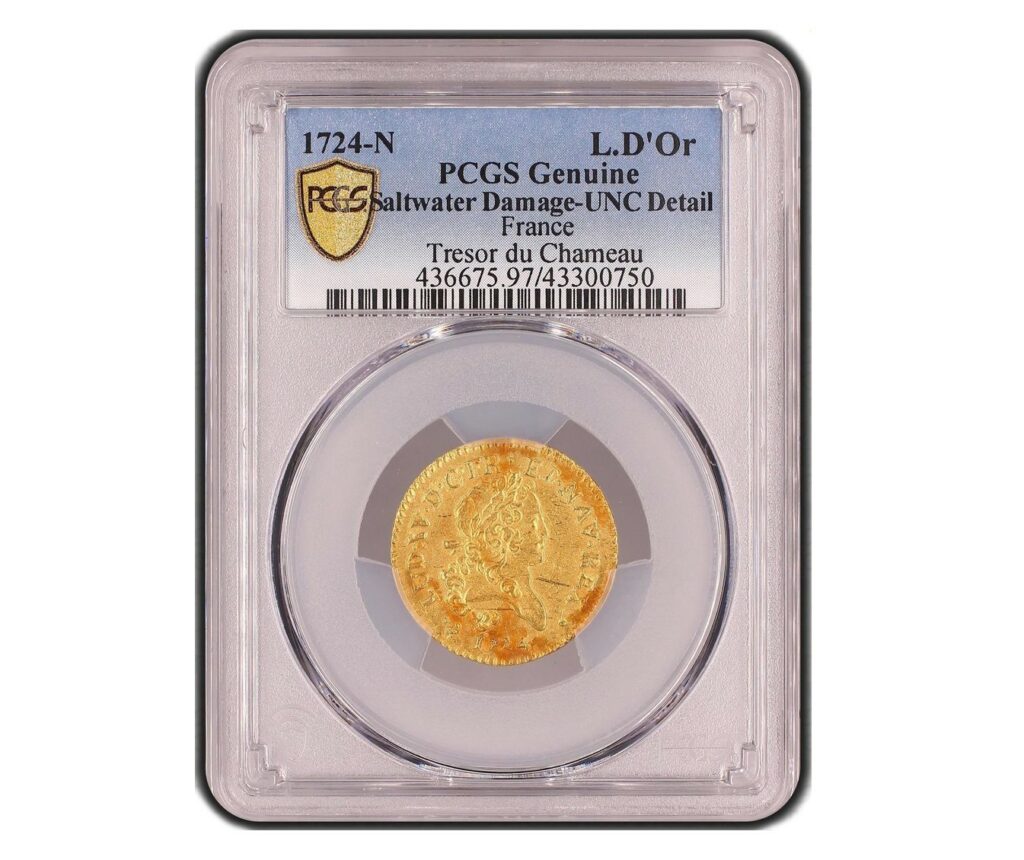

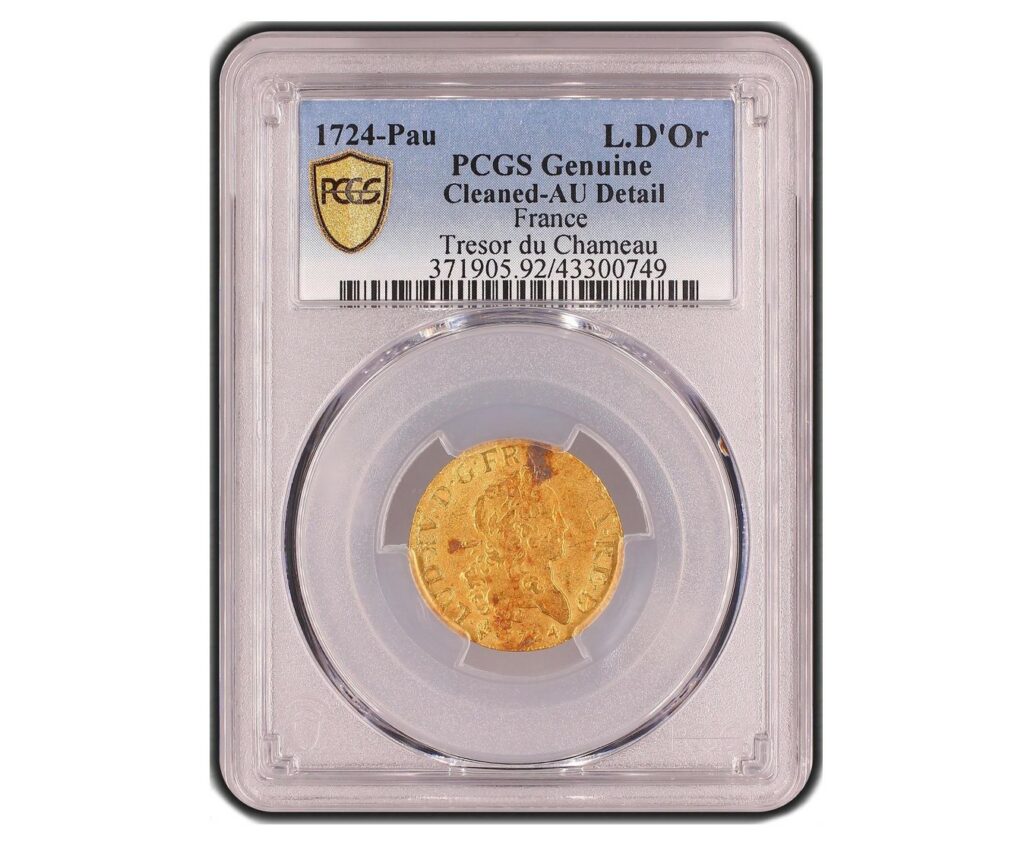

A total of 6958 silver coins spent around two and a half centuries in salt water, some of which being silver écus aux 8L of the reign of Louis XV. 494 gold Louis d’or Mirliton coins were also found. These were minted in 1723, 1724 and 1725 in 24 different workshops.

The gold coins are extremely well preserved, those in silver are less legible and welded together. It is useful to recall here that gold is a noble metal that alters much less than silver. Even if coins preserved in sea water are often recognizable by their condition (traces of corrosion, slightly matt patina), some gold louis d’or from the Chameau treasure kept an exceptional condition after staying more than 200 years at sea…

The recognized NGC and PCGS grading services certify and grade this type of coin preserved in sea water as : Salt Water / cleaned / grade with number. Pedigree “Tresor du chameau” written on slab.

Original old tag from New-York Parke-Bernet in 1971 certifies its origin.

Find all the collection treasures on our numismatic store, some of which are some superb gold Louis d’or Mirliton certified PCGS coming from the Chameau treasure trove. Enough to make your heart vessel capsize!

Census of Louis XV gold Louis d’Or Mirliton from the Chameau treasure | Sale by Sotheby’s New-York in 1971

Here is the census table of the gold coins that were sold at the 1971 New York auction. A total of 494 coins, minted in 1723, 1724 and 1725 in 24 workshops in several cities of France, were listed.

| Lettre Atelier | Atelier | 1723 | 1724 | 1725 |

| A | Paris | 18 | 7 | |

| B | Rouen | 2 | 3 | |

| C | Caen | 2 | 5 | |

| D | Lyon | 10 | 8 | |

| E | Tours | 2 | 6 | |

| G | Poitiers | 31 | ||

| H | La Rochelle | 17 | 46 | 37 |

| I | Limoges | 13 | 2 | |

| K | Bordeaux | 18 | 85 | 23 |

| L | Bayonne | 10 | 28 | |

| M | Toulouse | 5 | 32 | |

| N | Montpellier | 3 | 8 | |

| O | Riom | 3 | ||

| P | Dijon | 1 | ||

| Q | Perpignan | 1 | 2 | |

| R | Orléans | 2 | 2 | |

| T | Nantes | 12 | ||

| V | Troyes | 1 | ||

| W | Lille | 1 | 3 | |

| Y | Bourges | 3 | ||

| Z | Grenoble | 2 | ||

| & | Aix | 5 | 5 | |

| 9 | Rennes | 6 | 4 | |

| Pau | 6 | 14 |

Recensement des pièces d’argent du trésor du Chameau

Voici le tableau de recensement des pièces d’Écus aux 8L Louis XV.

| 1724 | 1725 | 1726 |

| H | G | H |

| K | H | |

| T | T | |

| I | ||

| K | ||

| O | ||

| T |

Two divisionals for another type are also listed: 1/12 d’écu à l’écusson de France 1719 K and 1/6 d’écu de France 1720 A.

Sources :

Wikipedia

Trésor des archives secrètes, Sabine Bourgey, 1988.

Catalogue de vente de 1971

New-York Times