Discover all the news and articles from TNUMIS Magazine exclusively

The sinking of the Schiehallion

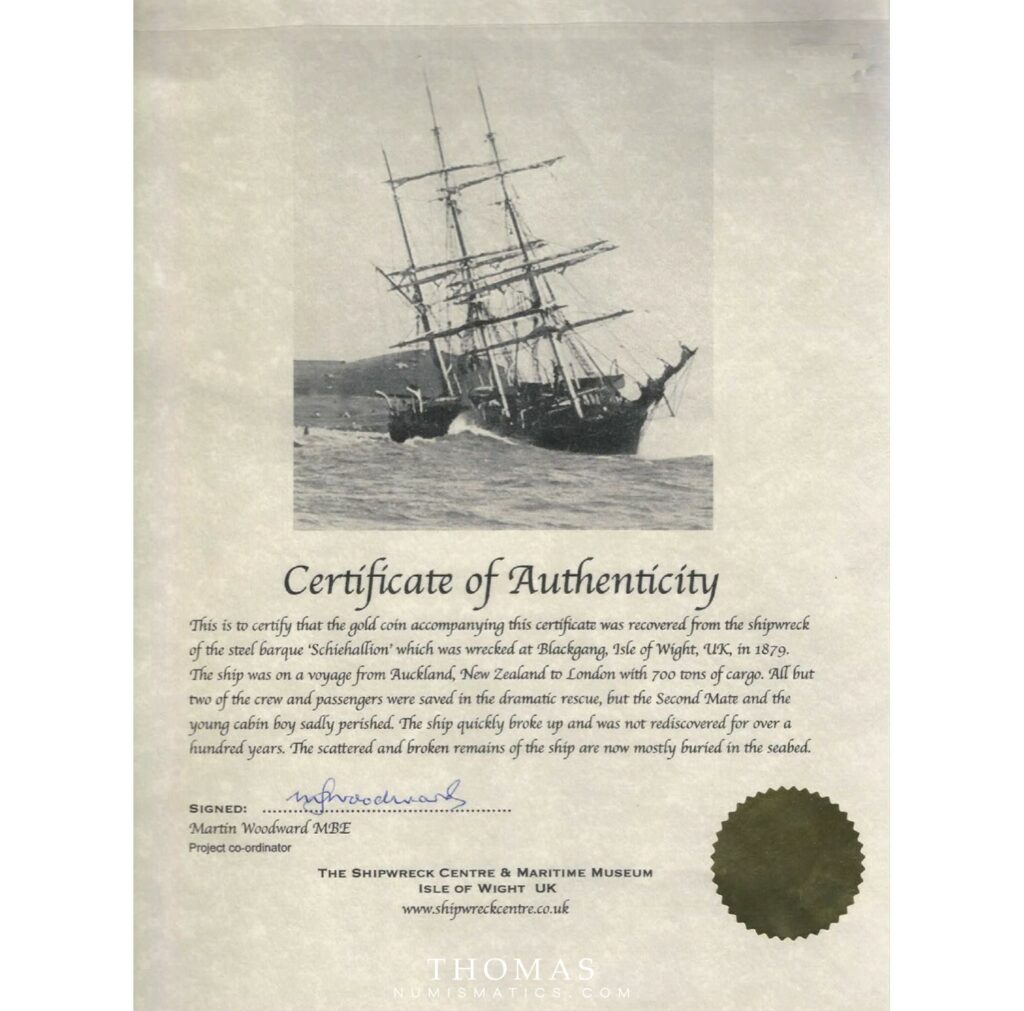

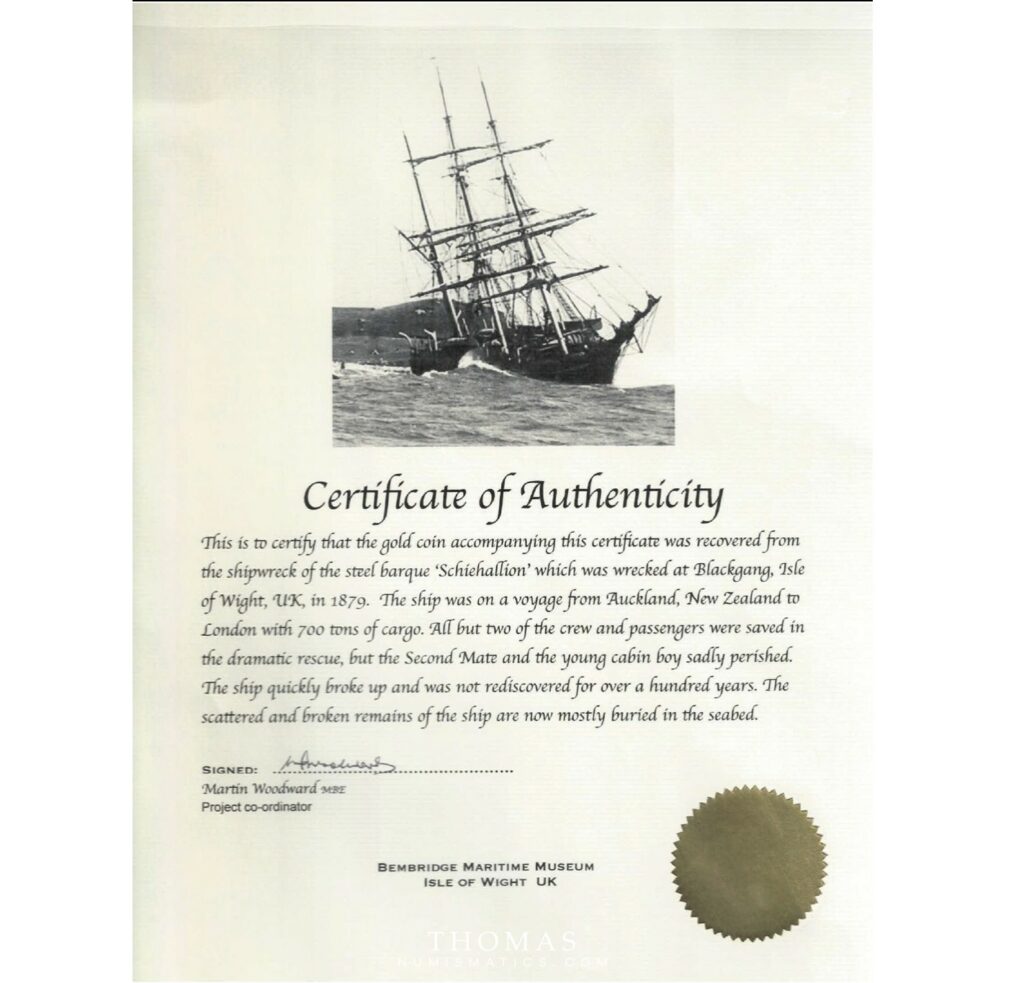

The Schiehallion, an English cargo ship, never completed its 1879 voyage. It ran aground in the English Channel, only a few kilometers before its arrival point. The result: two dead and part of its cargo washed out to sea. From the shipwreck of the Schiehallion, we have nevertheless recovered Victoria gold sovereigns and gold half sovereigns. Let’s take a look back at the tragedy.

A merchant ship

The Schiehallion was an iron-hulled sailing ship of relatively modest dimensions: 52.5 meters long and 8.6 meters wide. It was built in Scotland for Simpson & Brown Inc. and took barely a month to complete; the ship was launched on December 31, 1869 and sailed to London.

The Schiehallion was, in fact, intended for trade between the United Kingdom and New Zealand. From 1870 to 1879, it sailed many times between London and Auckland, long voyages interspersed with stops in Asia and Oceania. In 1875, it changed ownership and was sold to the shipping company Shaw & Savill.

The Schiehallion left Auckland for its last voyage on September 21, 1878. On board was a crew of sixteen, accompanied by thirteen passengers, including seven children. The cargo of approximately 700 tons consisted of goods from Asia and Oceania: kauri gum, wool, cotton, coconut oil, manganese, as well as silverware, jewelry and coins. Part of this cargo, insured for 16,115 pounds, or about 2.5 million euros today, was washed away on the morning of January 13, 1879.

The sinking of the Schiehallion

The ship ran aground at about 6:00 a.m. on the Isle of Wight, in the United Kingdom, at the very end of its journey. Many details of the sinking have come down to us, thanks in part to the account of Mr. Cruickshank, an agent of the Schiehallion.

The ship disembarked in bad weather, in the fog, on the beach of Blackgang on the Isle of Wight. The crew decided that it was too dangerous to launch the lifeboats because of the strong wind. The stormy seas lifted the hull, which hit the rocks. The solid ship did not break up immediately and gave the majority of the passengers time to evacuate. And this, thanks to the courage and bravery of the cook, David Moore. He decided to jump overboard with the lead line and managed to reach the shore, despite the extreme conditions of the icy water and the strong swell. Daniel Butchers, who had seen the accident from land, came to support him. He sent his son to alert the coast guard and ordered the passengers on deck to throw the hawser, which he tied to the rocks on land. Each passenger could then disembark, one by one, by holding onto the moored rope. In the turmoil, the first mate and a 14 year old New Zealand apprentice went overboard and were washed away by the current. All other passengers were saved.

The investigation following the accident

The English Board of Trade conducted an inquiry following the sinking of the Schiehallion. Many questions were asked about the ship’s trajectory from the island of Ushant, further south. When the ship hit the rocks, it was about 24 miles north of its supposed course.

The captain of the Schiehallion and co-owner of the vessel, John Levack, was found solely at fault and suspended for six months for his lack of care and vigilance. He had made an error in his estimate of the deviation when sailing up the channel, had not determined his position accurately, nor had he taken a hand sounding to measure the depth of the water.

David Moore was awarded the Royal Humane Society Bronze Medal for his bravery at a ceremony at the Royal Theater in London on October 15, 1879.

The cargo of the Schiehallion

The day after the tragedy, more than 200 crates of gum, 48 drums of tallow, 33 bales of cotton and several bags of cottonseed had been driven ashore by the sea. For about two weeks, one hundred local fishermen began a rescue effort. They managed to save a large part of the cargo and were thanked accordingly.

The Shipwreck Center & Maritime Museum on the Isle of Wright displays some of these recovered items. The most mysterious are a collection of lead crested badges. It is still not clear what they are for. A curator at the National Museum of Scotland believes that they are badges of Royal Naval ships, and that they may have been used to promote Scotland to Scottish expatriates in Australia and New Zealand.

Let’s look at the rare coins from the Schiehallion. A few coins were found after the shipwreck. We are fortunate to occasionally offer some of these rare coins for sale, such as this Australian Victoria gold sovereign, struck in 1872 in Melbourne and this British gold half sovereign, struck in 1844 in London. These coins have retained remnants of their original brilliance and a pleasing state of preservation after their prolonged stay in sea water.

Thomas Numismatics is a specialist in collectible treasures. We regularly offer coins from shipwreck treasures like this one. Contact us for any specific request.

Sources :

Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum

Papers past

Rootsweb