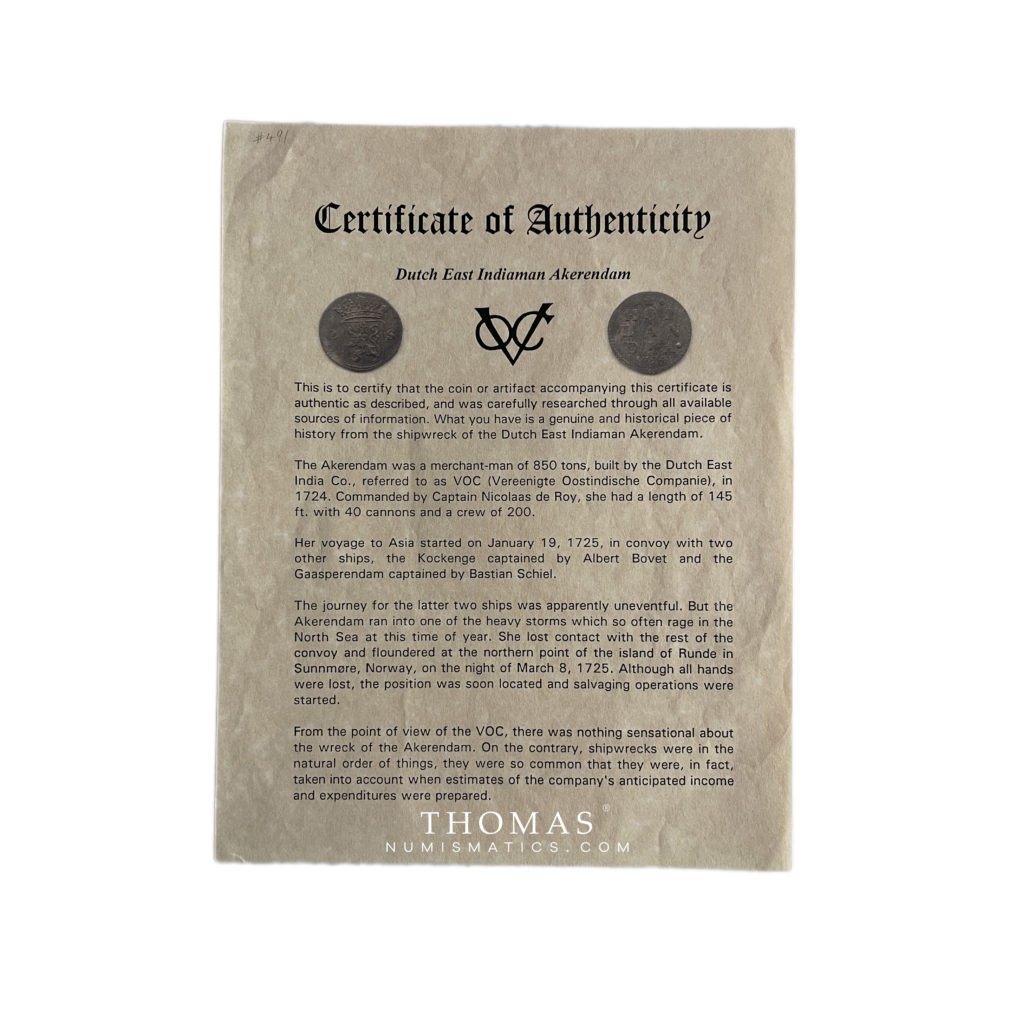

Discover all the news and articles from TNUMIS Magazine exclusively

The sinking of the Akerendam

On January 19, 1725, the Akerendam began its journey from the island of Texel in the Netherlands. It was accompanied by two other ships, all heading for Batavia, the former Jakarta and capital of the Dutch Indies. The Akerendam carried 200 crew members and a cargo of 19 chests of gold and silver coins. The trip did not go as planned and the convoy was hit by a blizzard in the North Sea. The Akerendam was blown off course and sank at the northernmost tip of Runde Island, Norway, on March 8, 1725. Although the ship was wrecked near the shore, there were no survivors.

The Akerendam, a merchant ship

The Akerendam was built in 1724, only one year before its sinking. It belonged to the Dutch company Vereinigte Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), which managed maritime trade with the Far East. The ships of this company regularly transported gold and silver to Batavia. Most coins were freshly minted and produced specifically for the Asian trade. The ships left with silver and returned with goods such as spices and other precious commodities to be sold in Europe.

Research after the sinking of the Akerendam

Very soon after the sinking of the Akerendam, the VOC company was informed of the disaster. They sent men to the Norwegian island to investigate. During the following weeks, bodies and debris were found near the island of Runde.

Only 11 days after the tragedy, on March 19, a public auction was held to sell the items found on the wreck. The items up for auction were canvas, iron straps and 50-liter barrels of French wine. The Dutch consul and representative of the VOC was present at this event. He visited the site of the Akerendam’s sinking and later reported observing “a large number of naked bodies, all badly broken, and a large quantity of personal property and goods”.

The search continued for Runde’s treasure. A few weeks later, Sheriff Ole Haugsholmen quickly finds a chest full of coins. A controversy broke out, as it was not clear who was responsible for the explorations. It was established that the Norwegian government would be responsible for the security of the site, while the men of the Dutch consul would carry out the salvage work under the direction of the local sheriff. During the summer and fall of 1725, four more chests were found. They were so corroded that one had its lid disintegrated when the men brought it to the surface.

As winter approached, the search ceased. Attempts were made to find other chests on the wreck the following year, but the explorations were unproductive. The wreck of the Akerendam was gradually forgotten.

The rediscovery of the Runde treasure in the 20th century

The Runde legends

In the 19th century, the Runde treasure was the subject of many legends. The inhabitants often found coins on the shore, but the details of the story were gradually forgotten. It is said that the coins belong to the Spanish Armada of the 16th century. Séverine O. Runde, born in 1839, told her granddaughter that her childhood walks were punctuated by finds of silver coins hidden among the rocks.

Explorations on the wreck of the Akerendam

Only on July 16, 1972, 250 years after the sinking of the Akerendam, three Swedish and Norwegian sport divers rediscovered the Runde treasure off the coast of Bird Island.

Stefan Persson saw a quantity of coins in a clearing. At the same time, the two other divers, Eystein Kroh-Dalen and Bengt-Olof Gustafsson discovered one of the 40 cannons of the Akerandam. They returned the next day with equipment to recover the treasure. For three weeks, the adventurers repeated the dives under police protection and recovered about half a ton of coins, as well as 32 other cannons.

The following year, the Bergen Maritime Museum revisited the site, covering a slightly larger area. The salvage operation resulted in the discovery of approximately 135 kg of coins. After registration at the Coin Cabinet, the Runde treasure was divided between the researchers who recovered 67.7%, the Norwegian state 25.4% and the Dutch state 7%. The total value is estimated to be about $10 million.

Norway deposited its treasure in the Numismatic Cabinet of the University of Oslo and in the Maritime Museum in Bergen. The discoverers’ share of the treasure was deposited at the Central Bank of Norway for several years, before being transported to Switzerland for auction in 1978. A Norwegian numismatist, Jan Olav Aamlid, bought about 6,000 gold and silver coins. He paid nearly a million dollars to acquire this part of the Runde treasure.

The treasure of the shipwreck of the Akerendam

A total of 57,000 coins were examined. More than 400 different types of coins were identified, 15 of which were unknown until this discovery.

Of the 6,624 gold coins, 6,505 are rare Dutch gold ducats, minted in Utrecht in 1724. The remaining 50,376 coins are silver. The majority are Dutch stuivers minted in 1724 as well.

Here are the details of the Runde treasure:

| Pièces d’or Utrecht ducat 1710 1 Gelderland ducat 1715 2 Gelderland ducat 1715 1 Hollande ducat 1715 14 Utrecht ducat 1715 1 Ouest-Friesland 2 ducat 1716 2 Ouest-Friesland ducat 1716 5 Utrecht ducat 1717 47 Utrecht ducat 1724 6505 Non-identifié ducat(2) 46 | Reales Mexique 8 real 8121 Mexique 4 real 2200 Mexique 2 real 13 Perou 8 real 21 Perou 4 real 7 Perou 2 real 3 |

Ducatons Pays-Bas Espagnol ducaton 3418 Pays-Bas Espagnol Hollandes 1/2 ducaton 705 Provinces-unies néerlandaises ducaton 4597 Provinces-unies néerlandaises 1/2 ducaton 127 Non-identifié ducaton 1168 Non-identifié 1/2 ducaton 135 | Petites pièces de monnaies Hollande scelling 1724 38 Hollande 2 stuiver 1724 29249 Divers Liège ducaton Année inconnue 1 Overijssel duit 1702 1 Hollande duit 1720 1 Hollande duit 1723 3 |

The cleaning of the Runde treasure

After 250 years spent at the bottom of the sea, the coins were covered with lime and stuck together. In order to identify the coins, they were separated from each other by dissolving the lime with formic acid. For many coins, this treatment was sufficient to allow their identification. The removal of the lime and a thin layer of rust revealed freshly minted coins.

In general, gold coins are very well preserved. The silver coins, on the other hand, are mostly badly corroded. The least affected were in the center of the heaps, surrounded by other coins, sand and lime.

Our store regularly offers superb examples of the Runde treasure that keep the memory of the Akerendam shipwreck alive.